Out of touch elites, information control a hammer for every nail, Indigenous Australians defy ideological pigeon-holing

The following post is syndicated from Rebekah Barnett

Australia emphatically rejected enshrining an Indigenous Voice to Parliament advisory body in the constitution at the weekend’s referendum, with a 60/40 split for No vs. Yes.

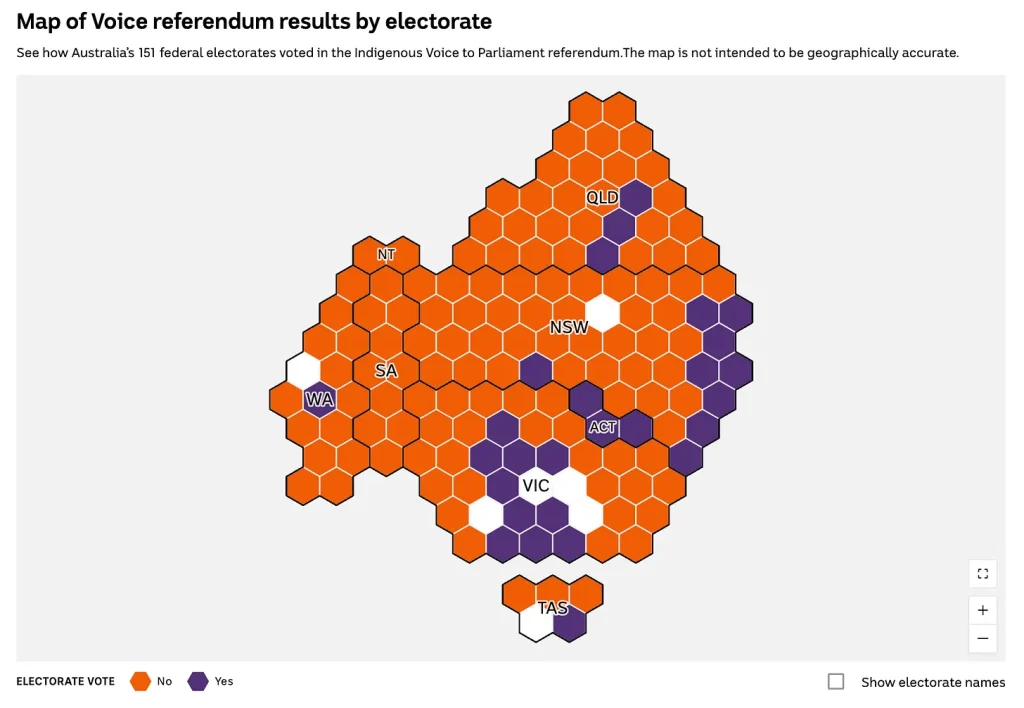

With most of the vote counted, it is predominantly the urbane, wealthy electorates clustered around major cities that voted Yes (purple), with by far the majority of electorates falling to No (orange. White is too close to call until counting finishes).

Yes and No campaign leaders, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese (Yes) and Shadow Minister for Indigenous Affairs Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (No) both acknowledged in their referendum night speeches that Australians all want what’s best for Indigenous Australians – they just have different ideas about how to achieve that.

Had this been the message at the heart of the referendum campaign from the beginning, the Voice debate might have been a unifying experience. But it wasn’t.

In a statement released over the weekend, Indigenous leaders in support of the Voice called the referendum result a “tragic outcome” and called for a week of silence in mourning.

It deeply saddens me that the statement is premised on an untruth.

It begins:

“Recognition in the constitution of the descendants of the original and continuing owners of Australia would have been a great advance for Australians. Alas, the majority have rejected it.”

That is completely untrue. People are grieving over a lie.

Recognition on its own had bipartisan support, which has historically been necessary to get a referendum over the line. Albanese knew that you can’t win a referendum without bipartisan support, but he forged ahead anyway. A referendum for recognition would have romped it in, of that I am certain.

Australians didn’t reject the recognition of First Nations people at the referendum. They rejected the double-barrelled proposition of recognition in the form of a Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution.

It was grossly dishonest for the Yes campaign to run a motte and bailey argument on this point, retreating to the motte (‘we’re only asking for recognition’) when the bailey (a permanent, ill-defined advisory body) proved hard to defend.

By doing so, they set up those Indigenous Australians who voted Yes to the Voice for a heavy sense of personal rejection should the majority of Australians vote No – which was always likely, based on Australia’s referendum history of what works (bipartisan support, long period of socialisation, clarity in messaging) and what doesn’t.

Commentary from Yes partisans who bought into the motte and bailey fallacy indicate that many of them too feel this devastation. Take this from the Guardian on the night of the referendum:

“Australia would either write another chapter in the history of reconciliation in this country, or fail a significant empathy test. Tonight, we’ve failed the empathy test.”

They really think the referendum was an empathy test. Incredibly, zero conception that one might have empathy but disagree on the specifics of the model proposed. People who think like this will be heartbroken at the prospect of forging Australia’s future in partnership with the 60 per cent majority who, in their estimation, proved at the polls to be deficient in empathy (and probably stupid and racist to boot).

It was also problematic that the Yes campaign ran on the false impression that First Nations people were unified in favour of the Voice. Right up until the day of the referendum, Yes campaign materials stated that 80 per cent of First Nations people supported the Voice.

This was misleading. The 80 per cent figure was based on two small online surveys run in January and March of this year, at a time when general support for the Voice was high. Support dropped away significantly by mid-year as Australians were given more detail about what the proposal entailed.

Being online only, the surveys necessarily excluded the voices of the most marginalised Indigenous Australians, those living in remote communities.

1 That the Yes camp presented as ‘fact’ a figure that excluded these voices in a campaign heavily focused on providing a voice to this same group is a sad indictment of the entire proposition put forward in this referendum.

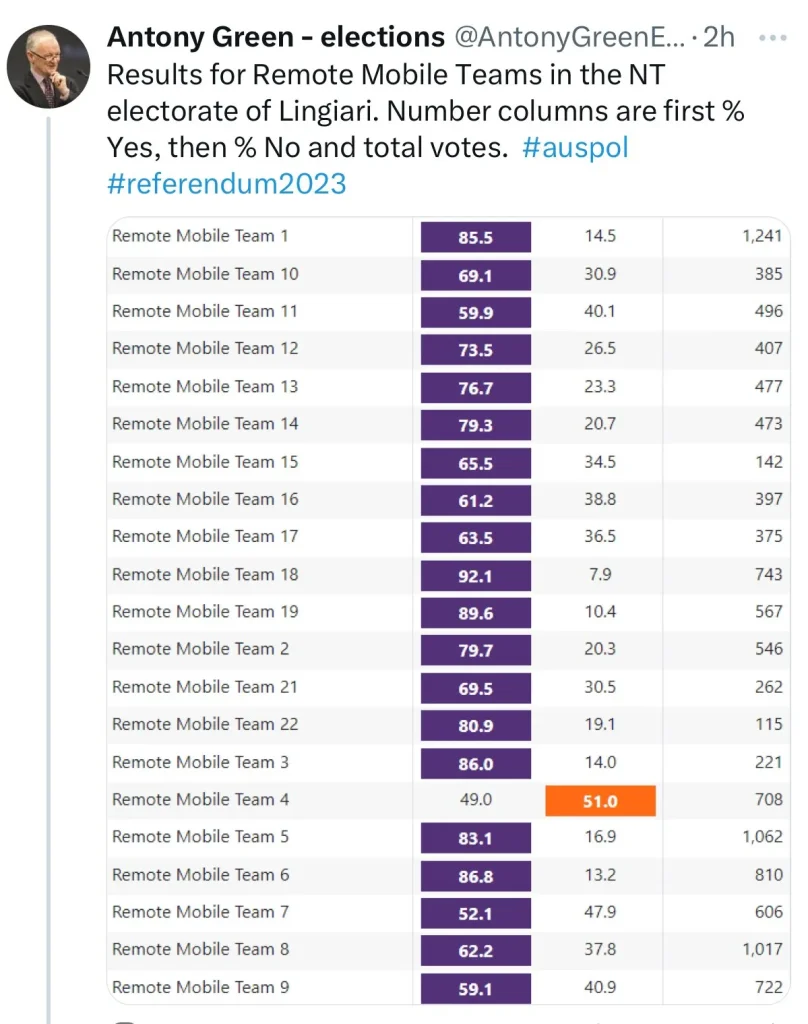

As it turns out, support for the Voice was higher in remote Indigenous communities than it was among the presumably more urbane Indigenous survey respondents, but still came in lower on average than the Yes campaign’s figure of 80 per cent.

Polling released just prior to the referendum day showed that Indigenous Australians were divided over the Voice with a 59/41 split for Yes/No. This compared to an overall split of 44/56 for Yes/No for the sample of Indigenous and non-Indigenous voters, combined. However this too was based on an online survey, and therefore subject to the same limitations as the earlier polls in failing to capture the voting intentions of First Nations people in the most remote communities.

Booth-by-booth results indicate that in remote areas populated predominantly with First Nations people, the Yes vote came in higher than in the wider electorate.

For example, in the Northern Territory electorate of Lingiari, where 40 per cent of the population is Indigenous, 21 of 22 remote mobile polling booths turned in a Yes majority, while the wider electorate voted 56 per cent for No. Totalling all booths, the votes collected by remote mobile teams in Lingiari went 69.3 per cent to Yes, 30.7 per cent to No.

In the West Australian electorate of Durack, which fell to No with 73 per cent of the vote, the Sydney Morning Herald reports that, “booths servicing Indigenous majority populations such as Halls Creek, Fitzroy Crossing and Wyndham all voted Yes to the Voice.”

However, the same report acknowledges that in other areas with a high proportion of Indigenous voters, votes for Yes came in under majority. In Parkes, in the small community of Boomi, just three of the 74 votes cast were Yes for the Voice.

In response to the higher Yes vote in remote polling booths with a significant proportion of Indigenous voters, Price made noises about the Australian Electoral Commission’s conduct in collecting these votes, saying, “One thing that I do know is the way in which Indigenous people in remote communities are exploited for the purpose of somebody else’s agenda.”

It has previously been reported that problems with literacy and lack of materials in appropriate languages can provide obstacles to voting for Indigenous Australians living in remote areas, but there is not currently any evidence that anything untoward happened during the Voice referendum.

Regardless, polling and remote booth results indicate that while First Nations people were more in favour of the Voice than the wider population, they were still divided.

If First Nations people were divided on the question of the Voice, how could anyone have thought that this referendum would succeed? The proposal was no doubt heartfelt and sincere in its conception in the form of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, but in terms of realpolitik, it was ill-conceived from the outset. It will take some time for the country to recover from the ugliness that this exercise brought to the surface.

As I predicted last week, the Yes campaign, lacking insight into their own failures, have already begun to blame the loss on ‘misinformation and disinformation,’ from the No campaign, calling for “repercussions.”

There’s no question that there was false and misleading information coming from both sides in the lead-up to the referendum. The questions are to what degree this impacted on the outcome, and what to do about it going forward.

Academic think-piece site The Conversation pontificates, “It’s open to question whether constitutional change of any kind can be achieved while voters remain so exposed to multiple versions of “truth.”

The implication is that limiting citizens’ access to multiple viewpoints may be the action required to achieve national cohesion on fractious issues. In light of the division within the First Nations community on the referendum vote, this ‘policy idea du jour’ among activists and academia belies a deeply paternalistic worldview that, ironically, smacks of colonialism.

‘Indigenous Australians who voted against the referendum proposal are too stupid to know what’s good for them and can’t discern between good and bad information. We need to control what ideas they’re allowed to be exposed to, for their own good.’

History tells us that limiting information flows to only allow a single state-approved narrative generally ends badly. Very badly. A more appropriate response to the problem of misinformation in a free and democratic society is democratisation of the information landscape.

Such an approach might include: public education in media literacy; limits on oligarchal media ownership; the fostering of respectful and nuanced discourse from our political leadership; a revival of local news, especially in print form so as to counter the click-baity 24/7 digital media cycle; and the decoupling of media and government as allies in narrative-control, so that the fourth estate can return to its intended mandate of holding truth to power.

As the dust begins to settle on the referendum, a clear picture is emerging. A political and activist class out of touch with the broad majority. An increasing preoccupation with information control as a means for explaining away their failures and imposing their best wishes on the population in the future. An Indigenous Australian population diverse in situation and outlook, by their mere existence defying the efforts of ideologues to treat them as a monolith by dint of their bloodline.

You can read more of Rebekah’s blogs on The Aussie Wire here